The Blue Continent in 2026: Navigating the Tides of Change

As the dawn breaks on 2026, the Oceania and Pacific region finds itself at a defining historical juncture. The "poly-crisis" of the early 2020s—characterized by pandemic recovery, inflationary shocks, and geopolitical polarization—has evolved into a more structural, albeit precarious, new normal. For the leaders gathering in Suva, Canberra, and Wellington, 2026 is no longer about crisis management; it is about implementation.

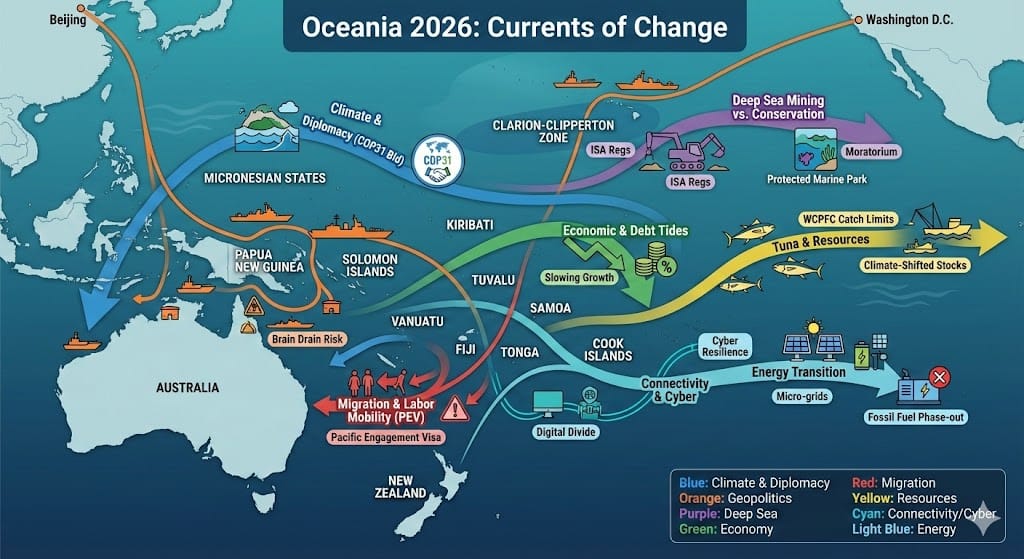

This year marks the convergence of several critical timelines: the operationalization of landmark climate funds, the potential commencement of deep-sea mining, and the maturation of new labor mobility architectures. Geopolitically, the region remains the fulcrum of the 21st century's "Great Game." Still, Pacific Island nations are increasingly asserting their agency, refusing to be mere chess pieces in a binary struggle between Washington and Beijing.

From the coral atolls of Tuvalu to the boardrooms of Sydney, the following ten trends represent the geopolitical and economic currents that will shape the Blue Continent in 2026.

1. The Climate Geopolitics of COP31

In 2026, climate change transitions from an environmental existential threat to the region’s primary lever of geopolitical influence. The centerpiece of this trend is the joint bid by Australia and the Pacific Island nations to host COP31.

While the bid was a diplomatic maneuver in 2024 and 2025, in 2026, it became a geopolitical reality test. If successful, the preparations will dominate the regional agenda, forcing a harsh spotlight on the dissonance between Pacific survival and Australian fossil fuel exports. We can expect Pacific leaders to use the "host leverage" to demand tangible domestic decarbonization commitments from Canberra, moving beyond the "green diplomacy" of previous years.

Crucially, 2026 sees the first disbursements from the Pacific Resilience Facility (PRF). After years of setup, this Pacific-led trust fund will finally begin flowing grants to community-level projects. This shifts the narrative from "accessing" complex global finance (a major bottleneck in the early 2020s) to "deploying" regional funds. However, with the World Bank forecasting a slowing of growth, the pressure on the PRF to deliver immediate economic stimulus alongside climate adaptation will be immense.

2. The Deep Sea Dilemma: Excavation vs. Conservation

2026 is widely predicted to be the "Year of the Seabed." With the High Seas Treaty (BBNJ Agreement) having entered into force in January 2026, the legal framework for the ocean beyond national jurisdiction is now in effect. However, this creates a friction point with the burgeoning deep-sea mining (DSM) industry.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) faces its moment of truth. After finalizing regulations in late 2025, the first commercial extraction applications for polymetallic nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone are expected this year. This issue threatens to fracture the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF). On one side, nations like the Cook Islands and Nauru view their seabed minerals as a sovereign path to economic independence—a "blue gold" rush essential for green energy batteries. On the other hand, a coalition led by New Zealand, Vanuatu, and Fiji continues to push for a moratorium, citing irreversible ecological damage.

In 2026, this debate will likely move from diplomatic halls to the water itself, with potential protests at sea and legal challenges lodged under the new BBNJ mechanisms. The trend here is the clash between two green goals: the need for critical minerals for decarbonization versus the imperative to protect ocean biodiversity.

3. The "War of 2026" Anxiety and Strategic Hardening

While actual conflict remains a worst-case scenario, the fear of conflict drives policy in 2026. The "War of 2026" scenarios—popularized by think tanks and wargames in previous years regarding a potential Taiwan contingency—have led to a hardening of military postures across the region.

For Oceania, this manifests in the "infrastructure of deterrence." We will see the acceleration of U.S. and Australian upgrades to bases in northern Australia (RAAF Tindal, Darwin) and arguably more sensitive advancements in joint facilities in Papua New Guinea (Manus Island).

However, the Chinese response in 2026 is likely to shift from seeking new military bases (which provoke backlash) to cementing "dual-use" influence: controlling ports, digital clouds, and policing standards. The "sovereign control over technology" will be the new frontline. We can expect Beijing to aggressively market its policing equipment and digital surveillance packages to Melanesian states dealing with internal instability, framing it as "social stability assistance" rather than military expansion.

4. The Migration Valve: The Pacific Engagement Visa in Action

Demography is destiny, and in 2026, the Pacific's demographic map is being redrawn by the Pacific Engagement Visa (PEV). With the ballot system now fully operational, up to 3,000 Pacific citizens (plus families) are moving to Australia annually as permanent residents.

While initially celebrated, 2026 will likely see the emergence of "brain drain" anxiety in source countries. As mid-career professionals—teachers, nurses, civil servants—win the ballot and migrate, smaller nations like Tonga and Samoa may face acute skills shortages.

Conversely, the Falepili Union between Australia and Tuvalu will face its first practical tests. As Tuvaluans begin to access the special mobility pathways, the administrative reality of a "merged" sovereignty regarding defense and security will undergo scrutiny. Does Australia’s veto power over Tuvalu’s security arrangements hold firm in the face of new commercial offers from non-traditional partners? The smooth (or rocky) operation of these visa schemes in 2026 will determine if they are expanded to other atoll nations facing climate displacement.

5. Economic Stagnation and the "Post-COVID Hangover"

Economically, the region faces headwinds. The World Bank and IMF projections for 2026 suggest a cooling of growth to approximately 2.6% for the Pacific Island countries. The post-pandemic tourism "revenge travel" boom has plateaued, and the cost-of-living crisis has settled into a permanently higher price floor for imported goods (fuel and food).

In 2026, debt distress moves from a risk to a reality for several nations. The grace periods on COVID-era loans are expiring. We should expect at least one major Pacific economy to enter restructuring talks, likely seeking relief not just from bilateral lenders like China (Exim Bank) but also demanding "climate-for-debt" swaps from multilateral institutions.

This economic fragility makes the region highly susceptible to "checkbook diplomacy." If traditional donors (Australia, NZ, US, Japan) cannot mobilize rapid budget support, Pacific governments may be forced to accept opaque financing packages that come with geopolitical strings attached, undermining regional cohesion.

6. The Tuna Wars: Climate Change Meets Fisheries Management

The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) faces a critical year. In 2026, the intersection of climate change and fisheries becomes undeniable. Warming waters are shifting tuna stocks eastward, moving them out of the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of some Melanesian states and into the high seas or the zones of Polynesian neighbors.

This "tuna migration" threatens the revenue base of countries dependent on the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA) vessel day scheme. In 2026, we will see intense diplomatic wrangling over "zonal rights"—can a nation claim fishing rents for tuna that used to be in their waters?

Furthermore, the South Pacific Albacore fishery remains in peril.8 With subsidies driving foreign fleets (largely Chinese and subsidized distant-water fleets) to overfish, Pacific nations will likely push for a hard "catch limit" rather than "effort limits" in 2026. This will be a major trade friction point, as sustainable management clashes with the industrial food security demands of Asia.

7. The Connectivity Gap: Hard Infrastructure and Cyber Vulnerability

Despite years of announcements, the "digital divide" remains a chasm in 2026. While major undersea cables (like the Google-backed projects) are nearing completion or coming online, the "last mile" connectivity remains poor and expensive in rural areas of PNG, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu.

In 2026, the conversation shifts to cyber resilience. As Pacific governments digitize their services (e-passports, digital land registries), they become prime targets for state-backed cyber espionage and criminal ransomware gangs. We can expect Australia to launch a dedicated "Pacific Cyber Shield" initiative (or expand existing ones significantly) to embed cyber-security experts within Pacific ministries. This is not altruism; it is an attempt to "patch" the back door to Australia’s own critical infrastructure.

8. Energy Transition: The Death of Diesel?

The energy transition in the Pacific is moving from "pilot projects" to "grid transformation." In 2026, the volatility of global oil prices (driven by Middle East instability) makes the reliance on imported diesel for power generation politically and economically untenable.

We will see a surge in "hybrid" micro-grid installations—solar plus battery storage—funded by the ADB and the new climate finance streams. The trend to watch is the trans-Tasman regulatory alignment. Australia and New Zealand are working to align their energy standards to allow for seamless investment in Pacific renewables.

However, a tension remains: Pacific leaders are demanding a "Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty." In 2026, this campaign will gain momentum, isolating Australia as a major gas exporter. The Pacific’s moral authority on this issue will be used as a diplomatic cudgel in every regional forum.

9. Fractured Regionalism: The "Ocean of Peace" vs. National Interest

The "Blue Pacific" narrative of unity is fraying. The Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), under the leadership of Secretary General Baron Waqa, faces the challenge of keeping the "family" together. The withdrawal of Kiribati in 2022 (and subsequent return) showed the fragility of the institution.

In 2026, sub-regional groupings—the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) vs. the Micronesian Presidents' Summit (MPS)—will assert distinct identities. The MSG is drifting closer to Beijing’s orbit, particularly on security cooperation, while the MPS (emboldened by the US Compacts of Free Association) aligns more closely with Washington.

The concept of the "Ocean of Peace"—declared by leaders previously—will be tested. Can the region truly remain an "Ocean of Peace" if individual member states sign bilateral security pacts that allow for the prepositioning of foreign military assets? 2026 will likely see a redefining of "non-alignment" to mean "multi-alignment"—taking money and security offers from everyone, much to the frustration of Canberra and Wellington.

10. Social Resilience: The Gender and Youth Dividend

Finally, the most underrated trend of 2026 is social transformation. The World Bank’s gender reports have highlighted that closing the labor market gender gap could boost GDP per capita by 20%. In 2026, we will see a wave of female political leadership and entrepreneurship, driven by digital access and targeted development programs.

Simultaneously, the "youth bulge" in Melanesia (PNG, Solomons, Vanuatu) is reaching a tipping point. With formal sector jobs scarce, the disillusionment of urban youth is a powder keg. In 2026, unless the labor mobility schemes (Trend 4) and infrastructure projects (Trend 7) deliver tangible income, we should prepare for localized civil unrest. This is not just an economic issue; it is a security one. The stability of the region depends not on the number of patrol boats, but on the number of jobs for 18-30-year-olds.

Conclusion

For Oceania and the Pacific, 2026 is a year of high stakes. The region is no longer a "strategic backwater" but the central stage of global climate and security politics. The risks are high: debt default, resource exploitation, and geopolitical fragmentation.

Yet, the agency of Pacific nations has never been stronger. By leveraging their vote at the UN, their control over the world's tuna, and their moral leadership on climate, the Blue Continent is navigating these tides with a clear destination in mind: survival and sovereignty.

The challenge for their partners—Australia, New Zealand, the US, and China—is whether they will help steer the ship or merely rock the boat.