The Pitcairn Paradox: Britain's Most Remote Dilemma

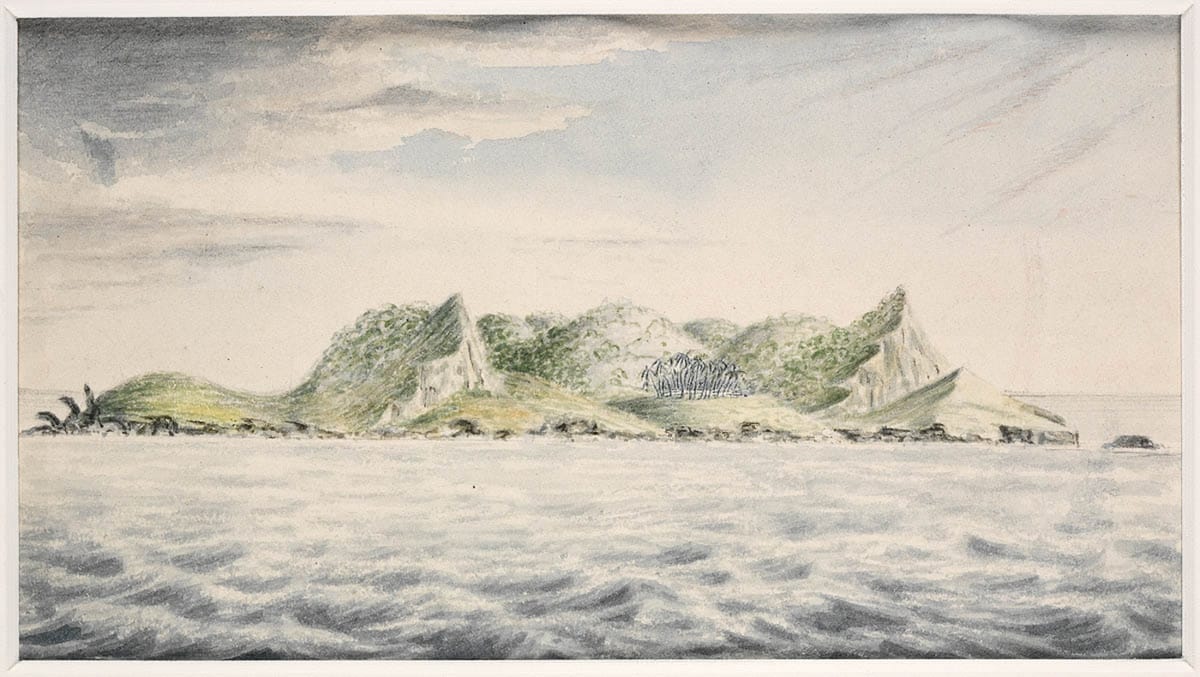

In August 2024, the Government of Pitcairn Islands quietly announced that its settlement process would be suspended pending review. For most British overseas territories, such administrative adjustments pass unnoticed. But Pitcairn is no ordinary territory. With fewer than 50 inhabitants scattered across 47 square kilometres of volcanic rock in the South Pacific—5,000 kilometres from New Zealand and 2,170 kilometres from Tahiti—it represents both a vestige of empire and a microcosm of the challenges facing micro-states in an era of demographic decline and fiscal constraint.

The suspension of settlement applications, except in "exceptional circumstances," marks a pivotal moment for this British Overseas Territory. It signals not merely bureaucratic recalibration, but an acknowledgment that the island's current trajectory—depopulation, economic stagnation, and growing dependency—may be unsustainable without fundamental policy revision.

A Colony Born of Mutiny

Pitcairn's origins are sufficiently dramatic to obscure its contemporary predicament. Settled in 1790 by mutineers from HMS Bounty and their Tahitian companions, the island remained largely unknown to the outside world until 1808. Today, most inhabitants trace their lineage to those original nine mutineers, creating a community of remarkable cultural continuity but perilous demographic fragility.

The very qualities that make Pitcairn unique—its isolation, its scale, its history—now threaten its viability. Younger residents depart for education and employment opportunities in New Zealand, Australia, or Britain itself, and few return. Birth rates have plummeted. Economic analyses suggest that by the mid-2020s, pensioners may outnumber working-age residents, inverting the dependency ratio to catastrophic effect.

The Imperial Burden

For Britain, Pitcairn presents a peculiar challenge. Unlike Gibraltar or the Falklands, which possess strategic value, or the Cayman Islands, which generate substantial revenue, Pitcairn offers little beyond moral obligation and historical sentiment. Yet that obligation is real. Under international law, Britain bears responsibility for the territory's governance, security, and welfare—a commitment that costs the UK exchequer millions of pounds annually in aid, infrastructure support, and administrative oversight.

The logistics alone are formidable. Pitcairn has no airport and no harbour capable of accommodating large vessels. Supplies arrive quarterly via chartered freighter, weather permitting. Medical emergencies require evacuation by sea or, in extremis, costly helicopter transfer from passing ships. Education for the handful of school-age children must be provided locally or subsidised abroad. The island's satellite internet connection, essential for modern governance, requires continuous UK funding.

Britain's dilemma deepens when governance failures occur. Following serious criminal cases in the early 2000s, Westminster was compelled to establish a dedicated judicial system, complete with visiting judges and prosecutors, at considerable expense. The episode underscored an uncomfortable truth: Britain cannot simply walk away, yet effective governance of a community so small and remote stretches conventional administrative models to breaking point.

The Settlement Paradox

Therein lies the paradox confronting Pitcairn's administrators. The island desperately needs new residents—preferably young families with skills and capital—to reverse demographic decline. Yet each new settler exerts disproportionate impact on infrastructure, social cohesion, and the delicate cultural fabric of a community where everyone is related by blood or marriage.

Previous settlement drives have yielded mixed results. Attracting self-sufficient pioneers to a roadless island accessible only by sea, lacking employment opportunities, and offering subsistence living rather than modern amenities, proves remarkably difficult. Those who arrive often leave within months, deterred by isolation, limited economic prospects, or the challenges of integrating into a tight-knit community with its own customs and hierarchies.

The current review appears to reflect hard lessons learned. Rather than encouraging indiscriminate settlement, administrators now seek to identify what kind of newcomers the island can realistically absorb, what infrastructure must be in place before they arrive, and how to balance growth with sustainability. This represents a maturation in policy thinking, but also an acknowledgment that Pitcairn cannot simply grow its way out of trouble.

Economic Realities

Pitcairn's economy has always been marginal. Traditional revenue sources—postage stamps for philatelists, internet domain registration fees, handicraft sales—have declined with changing global markets. Tourism remains minimal; the island's remoteness and lack of accommodation limit visitor numbers to a few dozen annually, typically passengers on expedition cruises who land for a few hours.

More ambitious proposals have foundered on geographic and economic reality. Suggestions for aquaculture, niche agriculture, or digital services collide with the costs of freight, the limitations of satellite connectivity, and the absence of capital or expertise. The island's surrounding waters, protected as one of the world's largest marine reserves, offer environmental prestige but little immediate economic benefit to residents.

For Britain, this creates a fiscal trap. Continued subsidies are necessary to maintain even basic services, yet increased investment seems unlikely to generate self-sufficiency. Westminster's tolerance for such arrangements has limits, particularly as post-Brexit Britain reassesses its global commitments and domestic constituencies question expenditure on territories few voters could locate on a map.

Environmental and Strategic Considerations

Yet abandoning Pitcairn would carry costs beyond the moral. The Pitcairn Islands Marine Protected Area, established in 2016, spans 834,000 square kilometres—larger than France—making it one of the world's largest ocean sanctuaries. Its management requires a permanent local presence and UK commitment to monitoring and enforcement.

Moreover, in an era of renewed great-power competition in the Pacific, even tiny territories acquire strategic significance. China's expanding influence across Pacific island states has prompted renewed attention to sovereignty and presence. A depopulated or abandoned Pitcairn could complicate Britain's claims or create opportunities for other actors. While such scenarios remain speculative, they feature in Whitehall discussions about the territory's future.

The Path Forward

The settlement review, then, represents more than administrative housekeeping. It signals an attempt to reconcile competing imperatives: the need for population growth against the limits of infrastructure; the desire for self-sufficiency against economic reality; Britain's obligations against its constrained resources; and the preservation of a unique community against the homogenising pressures of globalisation.

No solution will satisfy all stakeholders. Increased UK investment might stabilise the population but would deepen dependency. More selective immigration might preserve community character but fail to reverse demographic decline. Encouraging departure and managed depopulation might be fiscally rational but would extinguish a unique cultural heritage and create awkward international precedents.

For now, the suspension of settlement applications buys time for reflection. It acknowledges that Pitcairn's future cannot be secured through improvisation or wishful thinking. Whether that future involves a renewed, sustainable community or a more fundamental reckoning with the limits of micro-state viability remains to be seen. What is certain is that Britain, however reluctantly, will bear responsibility for whatever comes next. The mutineers' descendants may have chosen isolation, but their colonial metropole cannot.